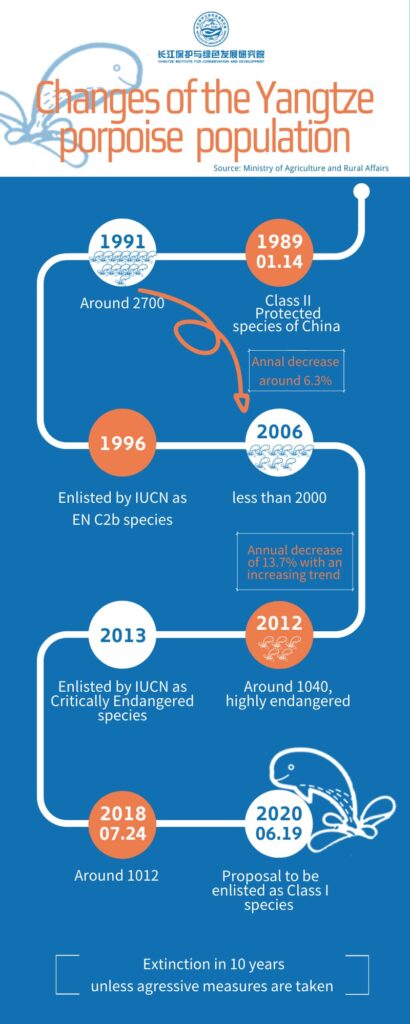

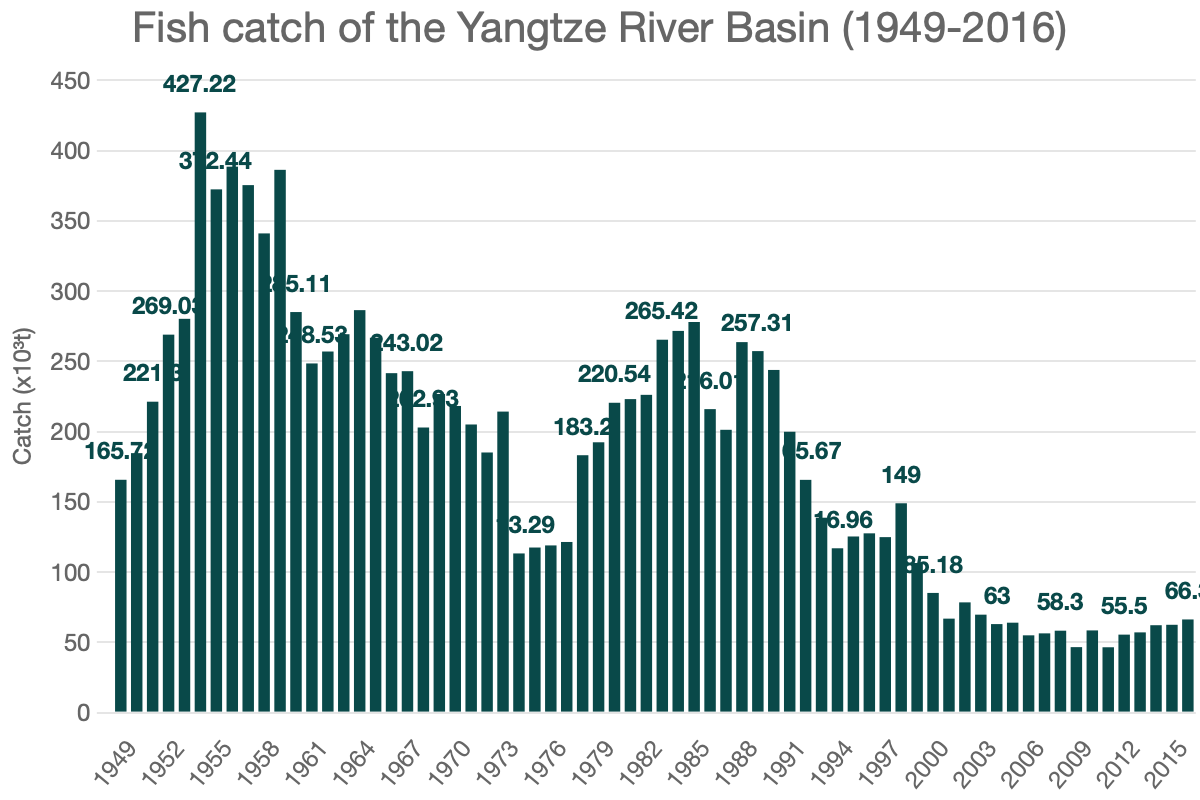

The Yangtze is China’s largest river, and its biodiversity not only?supports?local aquatic ecosystems but also ensures the food security of the region. As fish take the middle to top layers of the?food pyramid, their protection is among “the direct and most important goals“.?Data from research?show that there are more than 400 fish species in the Yangtze River Basin, among which around 350 are freshwater ones and 156 are unique to the region. However, the?fishery catch of the river basin has been rapidly declining?within the last few decades. This, on the one hand, proves the depletion of fishery resources of the Yangtze, and on the other, reveals the loss and degradation of biodiversity and environmental health of the river.

As China vows to “put the ecological restoration of the Yangtze at an overwhelming position“, fishing has been completely banned on the river since 1 January 2021, and the ban will stay in pace for a duration of ten years. The 10-year fishing ban gives the river a valuable chance to rehabilitate. However, it also means around 231,000 fishermen are forced to give up their walks of life to start brand new ones ashore.

As supporting policies for the fishing ban, the Chinese Ministries of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Finance, and Human Resources and Social Security jointly announced in January 2019 the Implementation Plan for Fishing Ban and Fishermen Compensation of the Yangtze River. The plan aims to “guide former fishermen for re-employment or self-employment”, and “ensure the basic livelihood of those of them difficult to be re-employed”. The majority of responsibilities for compensating fishermen, according to the plan, lies with local governments, and it encourages local governments to “adjust measures to local conditions and implement policies with flexibility”.

The fishing ban has been put in place for more than a year. Have the fishermen been successfully re-employed? Have they been satisfactorily compensated? A group of students supervised by Prof Guiliang Tian spent ten months in 2020 interviewing former fishermen in Jiangsu Province. Their research won a second prize of the 17th Challege Cup in Jiangsu. Prof Tian, and Zheng Wu, Lan Liang and Yunxiang Bao, three members of the team, shared their opinions and stories.

What attracted your attention to the fishermen? How is their compensation going?

The protection of aquatic biodiversity of the Yangtze lies at the very centre of the protection of the river. As species at the middle to top of the food web, protection of fish should be a core component of the centre. There are more than 400 fish species, 350 freshwater ones among them, in the Yangtze, and most of them can be found in the river section in Jiangsu Province. The continuous over-fishing and habitat degradation have made the river almost completely “fish-free”. Therefore, the fishing ban is an important measure to allow them to recover.

The fishing ban means people who were originally employed in the fishery industry must give up their ways of life. This ban is a very typical administrative intervention, and its impact is profound and significant because it is being implemented very thoroughly. The fishery industry is a highly specialised one. Therefore, fishermen tend to depend on it exclusively for living. They are usually older in age, less educated, and supporting large families. Moving them ashore means asking them to give up their means of production as well, like their boats and fishery tools. Some of them even possess no land or house, and it therefore is a real problem for them to sustain their lives and living standards. China in 2021 declared to have achieved its first centennial goal of a moderately well-off society. Whether moving fishermen out of fishery would drive them back into poverty would be a worthy question.

By December 2020, Jiangsu has completed the relocation of fishermen. According to the local government, all fishermen have stopped fishing and all of them have moved ashore, which is in a leading position in the country. However, these two “alls” do not necessarily mean all fishermen have been re-employed. They have only stopped catching fish for a living. The eight municipalities of Jiangsu along the Yangtze (Nanjing, Zhengjiang, Yangzhou, Taizhou, Changzhou, Suzhou and Nantong) amass a total of more than 40,000 fishermen. Our survey shows that more than 75% of them are more than 46 years old. These fishermen are difficult to be re-employed because they usually lack skills other than fishing and have difficulties learning other skills. About 60% of them have been re-employed, according to our survey, but most of them are re-employed in labour-intensive industries with evidently lower income than before.

Are there any shortcomings in the current compensation scheme of Jiangsu? What do you think is the key problem here?

Currently, the policies of the eight riparian municipalities of Jiangsu are mainly providing one-time compensation to fishermen based on records that have been set up beforehand. Compensation plans differ among the municipalities, ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands (Chinese yuan), due to different economic strengths. They also provide some help in re-employment, which, however, doesn’t take into consideration differences between families and individuals, and therefore, lacks accuracy and individuality. Our survey shows that there are huge income differences between fishermen. Some of them, who are technology-empowered, have an annual income of around 300,000 yuan, while others, who are older and more comfortable with traditional fishing tools, could only earn ten to twenty thousand yuan annually. Therefore, they have completely different needs.

The current policies target fishermen with fishery permits only. However, as we found in our survey, not all fishermen possess such permits. Those fishermen without permits are in a grey area and not included in the compensation schemes. There is no readily available information about their number and distribution either. As they are not compensated and helped, they are very likely to return to their old business and discount the effect of the fishing ban.

For the source of funding of the compensation, the current policies rely almost exclusively on governmental funds. This is somewhat a heavy load for some local governments, or in some cases, utterly inadequate. For the sustainability of the policies, it is recommended to take advantage of the “users pay” principle. While making use of governmental spending, policy innovations to allow more compensation from beneficiaries of the fishing ban to fishermen.

The team proposed a way to assess the compensation by the satisfaction of the fishermen. Why is that necessary?

Quitting fishing means changing the means of living for fishermen. How could we measure the monetary value of living? This is somewhat similar to valuing life. How much does life cost? Obviously, this is something very difficult to measure with some quantitative standards. In many studies of ecological economics, economists often use people’s willingness to pay1 to measure the value of resources that are difficult to value. Inspired by this concept, we want to assess the compensation policies by the satisfaction of fishermen. In plain words, we try to look at how much compensation would make them happy.

Moreover, from the perspective of policy implementation, the fishermen are people who are actually taking the actions. If the fishermen are not motivated or proactive for the implementation [of the ten-year fishing ban], the policies would be difficult to sustain, which is against the original intent of the fishing ban. China’s present policies for ecological conservation lay high emphasis on the role of the government and the market, yet the involvement and participation of the public are inadequate. For the ten-year fishing ban, if we are to invite fishermen to proactively participate in the policy, we have to meet their demands first. Sufficiently involving the public and making the policy design into a participatory one are important steps to make the policy sustainable. This is another reason we think assessment based on fishermen’s satisfaction is important.

The underlying rationale of Pay for Ecosystem Services is compensation from beneficiaries. In the case of the fishing ban, how do we understand the ” beneficiary – compensated” relationship?

The fishing ban could be understood as a typical practice of ecological conservation that has obvious externalities2. It, to a considerable extent, benefits many industries or communities, including certain riparian residents. It is even beneficial for future generations by saving biodiversity and the environment, and opportunities for sustainable development. Given this, we think, for beneficiary communities who are difficult to identify, we need government funds [for compensation]. However, for those beneficiaries easily identifiable, for example, real estate developers, tourism, water suppliers and waterborne transport, we need to ask them to share their benefits. The ecosystem services provided by the Yangtze, its value takes in direct or indirect forms. Apart from direct values like the scenery, indirect values exist in cost savings in, for example, water treatment, water transport, etc. Their benefits from cost saving should be shared [with fishermen who are bearing the loss]. On the other hand, the catering industry, though they are no longer allowed to sell river fish from the Yangtze, should not dodge their responsibilities as they have been benefiting from it for quite a long time.

Your team proposed a compensation framework based on sustainable means of living, in which, apart from monetary compensation, you also think it is necessary to include social compensation. How do we understand that? How could we help former fishermen to get re-employed?

We think, compensation for the fishermen should include not only monetary but also non-monetary (social) compensation. The social compensation should include career training, child education and pensions. There are three reasons for such consideration. First, a major portion of the former fishermen are in middle or old age. They would have to face the question of how to make a living after quitting fishing. Second, the fishing industry is quite unique because fishermen usually spend days or even a whole month on water, and therefore have a very limited social network. Third, fishermen on average are in a lower social class. As the saying goes, fishermen usually have “no roof over their heads, nor land under their feet”. They might be subject to discrimination or prejudice when they quit fishing and hunt new jobs. These reasons make fishermen difficult to sustain their living, and therefore monetary compensation isn’t sufficient for them.

According to our survey and analysis, the income difference between fishermen is mainly out of three factors. The first one is their region. For example, fishermen from Suzhou and Changzhou are earning more than others. The second is age. Among Suzhou and Changzhou fishermen, those who are in their thirties are commonly making a higher income from the fishery. The third is education, but the third factor is found to be less significant than the other two, which need our attention. Given these factors, the compensation for fishermen should, first, ensure they could sustain their basic living, second, improve their social status, and third, offer them tailored help to get re-employed.

The re-employment of former fishermen cannot be accomplished overnight, and needs actions from three dimensions. Social security comes first. We need unemployment insurance for them on one hand, and supporting policies for their re-employment on the other, like, for example, income tax deductions for fishermen themselves or their employers, or special allowances for the latter.

The second goes the willingness and skills of the fishermen to get re-employed. This would first require a lot of training and information sharing for them through public systems, in particular those fishermen who are willing to and have sufficient skills to get re-employed. Second, apart from in-person events like job fairs, the internet should be made full advantage of for their re-employment. Third, more financial help should be offered to them, like, for instance, low interest or interest-free loans for their new startups to incentivise their own entrepreneurship. A good example we know is the loans provided by the Luhe district of Nanjing for fishermen to start their own businesses.

Industry development is the third dimension. The re-employment of fishermen usually falls into two categories. They could still be employed in fishery-related jobs. For example, some of them are taking up new jobs in fish farming, fishery inspector, and so on. Others might have to move on to new industries which suit their skills. For example, the Jiangyang District of Luzhou, Sichuan offers programmes where former fishermen combine their skills with agriculture to develop new job opportunities. They raise fish in rice paddies, make aquaculture products and develop angling business.

How should the private sector play a role in the resettlement of former fishermen? How is Covid impacting that role?

The Covid pandemic and much uncertainty out of that have impacted the private sector significantly. Small and medium-sized businesses, who are more vulnerable to risks, are impacted in a particularly bad way. In 2021, China’s GDP grew by 8.1%, and that growth is expected to be further lowered to 5.5% according to Premier Li Keqiang’s Government Work Report. This echoes with the risk of a recession of the global economy. But on the other hand, we should also see that China’s economy is with good resilience. More and more businesses are adapting to the situation under a pandemic to maintain their operations, and small and medium-sized businesses are very flexible in this regard. Our survey found that, despite the slow down of the economy, some companies are still short of labour, and are willing to find stable labour sources. They could offer a considerable number of vacancies, including positions suitable for former fishermen. As China’s economy grows into maturity, more businesses are paying more attention to their social responsibilities. They would take on more ESG3 agendas, and are willing to help those in need.

But a major problem lies with how to match the needs of the businesses with that of the fishermen. This would require a lot of information sharing to match the needs of both parties. Additionally, because of the pandemic, many job fairs or training have been moved online, and therefore, many elderly or less educated people are missing more opportunities. The governments have to play a role in match making. Connecting these two parties would allow businesses to tailor the training of fishermen to save time and cut costs.

Additionally, on the government side, to incentivise the resettlement, we would call for tax deductions or cost allowances for small and medium-sized businesses that are willing to take on former fishermen.

In the compensation and resettlement, how could fishermen provide help to each other? Is there any organisation offering such opportunities?

Fishermen are unique because many of them run fishery as a family business which has been passed on for many generations. Groups are formed based on families and there is little connection between different groups. There are few organisations who are facilitating this. We only found an organisation called China Fishery Mutual Insurance Association who, in 2020, started an insurance scheme based on mutual help. However, the scheme is targeting fishery accidents only, and the fishing ban, regarded as a force majeure, is not included in its coverage. For the fisherman community, we would like to call on these organisations for more attention in facilitating such cooperation. They could play an important role in providing support in either physical resources or organising to help fishermen adapt to new situations, and sustain a stable living.

How would you like to convince government officials to accept your ideas in a simplest way?

The implementation of the fishing ban should?pay attention to the sense of gain of former fishermen. They are not merely people who are implementing the policy, and their compensation and resettlement should not make them willing to contribute and benefit from the policy. This relies on policy innovations to diversify and increase their compensation, support their re-employment, and improve social inclusiveness for them.

Related scientist

Notes

1 Willingness to Pay is an economic concept. It means how much a person values a good. In plain language, it means the maximum amount of money he or she would pay to acquire a unit of the good. See The Economy: Economics for a changing world.

2 Externalities is an economic concept which is also known as “external effect”. Externalities are positive or negative effects of a production, consumption, or other economic decision on another person or people that is not specified as a benefit or liability in a contract. It is called an external effect because the effect in question is outside the contract. See The Economy: Economics for a changing world.

3 ESG is the abbreviation for Environmental, Social and corporate Governance. ESG agendas evaluate how a corporation works on behalf of social goals. ESG goes beyond the goal to maximize profits for the corporation’s shareholders.

]]>The?Yangtze River Protection Law?is the first basin law of China. Why does China need a special law to protect the Yangtze River??

As per defined in the Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China, the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee shall have the right to make laws; the State Council shall have the right to make administrative rules; the Local People’s Congress and its Standing Committee shall have the right to make local regulations, autonomous regulations and separate regulations within their statutory authority (details are shown in Section I, Chapter IV of the Legislation Law); each department of the State Council shall have the right to make departmental rules and local governments shall have the right to make their rules within their statutory authority (details are shown in Section II, Chapter IV of the Legislation Law); wherein, laws have higher validity than administrative regulations, local regulations and rules.

The Yangtze River Protection Law is the first basin management law of China made by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Before the promulgation of this Law, China did not have any specific basin legislation. Thelaws applicable to basin management (including the Yangtze River Basin) only included the Water Law, the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law, the Waterway Law, the Law on Ports, the Law on Flood Control, the Water and Soil Conservation Law, the Land Administration Law, the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law, the Mineral Resources Law, the Wild Animal Conservation Law, the Fisheries Law, the Forest Law, the Grassland Law, the Urban and Rural Planning Law, the Environmental Protection Law, the Law on Environmental Impact Assessment, the Law on the Prevention and Control of Environment Pollution Caused by Solid Wastes, as well as general laws in terms of constitution, civil law, administrative law, criminal law, and some administrative regulations, local regulations and rules. The administrative regulations specially made for basins included the Regulation on the Prevention and Control of Water Pollution in the Huaihe River Basin, the Regulation on the Administration of the Taihu Lake Basin, and the Regulations on Administration of Sand Excavation in the Courses of the Yangtze River, and wherein, the Regulation on the Prevention and Control of Water Pollution in the Huaihe River Basin has gone invalid; in addition, there were some local regulations and rules made on basins.

The Yangtze River in China has superior natural conditions: Being more than 6,300km long, the Yangtze River has a total water volume around 961.6 billion m3, which accounts for 36% of the total river runoff in China, and ranks the third place in the world. It is only second to the Amazon River and the Congo River (Zaire River), both covered by equatorial rain forest. The Yangtze River Basin has a unique and complete ecosystem, which has unique and self-sustained eco-system services. From source to sea, the Yangtze River is high in the west and low in the east and forms a three-stage ladder. Parts of the river bed have big gradients, extensive beaches habitats, fast-flowing current, and abundant water resources. In the Yangtze River Basin, there are more than navigable 3,600 river, accounting for 70% of national totalmileage of inland waterways. Its middle and lower reaches, in particular, are renowned as the “Golden Waterway”. Large ships may safely navigate through these reaches all the year around thanks to the small gradient and the deep and broad river.

Because of its superior natural conditions, settlements on the banks of the Yangtze River are extensive. So far, the Yangtze River Basin has a population of around 400 million, accounting for 1/3 of the country, and the average population density here is more than 220 per km2. In the Yangtze River Delta, Chengdu Plain and the Middle and Lower Yangtze Plain, the population density is up to 600-900 persons/km2. It even reaches up to 4,600 persons/km2 in Shanghai, which is the most densely populated area in China. In terms of economy, according to Luo Guosan, the Director of the Infrastructure Development Department of National Development and Reform Commission, at the News Conference on January 5, 2021, “the proportion of the total economy in the Yangtze River Economic Belt to national total increased from 42.3% in 2015 to 46.6% in the first three quarters of 2020. Emerging industrial clusters had remarkable driving effects, and industries such as electronic information and equipment manufacturing accounted for more than 50% of the country respectively”.

The growing population and economy, and the long-term excessive development have overwhelmed the Yangtze River. Therefore, “the Yangtze River is ill, and seriously sick.” To be specific, the first is the crisis in water availability. The competition for water resources, the over-exploitation of hydropower, and regional climate changes, etc. have led to continued decrease of water availability in the middle and lower reaches, frequent drought of Dongting and Poyang Lake, and even dry-up of rivers in many places. The second is serious pollution. Along the banks of the Yangtze River, there are five steel and iron bases, seven refineries and more than 400,000 chemical enterprises, and more than 6,000 large-scale sewage outfalls, through which, nearly 40 billion tons of waste water and sewage are discharged into the River every year. Coupled with non-point source pollution from agriculture and other sectors, the pollutants have by far exceeded the River’s capacity. The third is the occupation of water areas. Many water-bodies have been converted for urbanization and real estate development, leading to the significant reduction of water areas and wetlands; siltation and illegal sand mining have resulted in the serious damage to the functions of the river system. The fourth is water loss and soil erosion. The middle and upper reaches of the Yangtze River are national ecological conservation areas, but the problem of poverty needs to be be solved in these areas (where there were 258 poverty-stricken counties according to national data, accounting for 43.6% of the country), since a vicious circle of “poverty-development-degradation” has been formed here. The fifth is the excessive development and utilization of waterway resources. The juxtapose of these factors has resulted in the sharp decline in resource availability, environmental health and ecological services of the Yangtze River, the difficulty in the supply of clean drinking water, the extinction of certain species or even complete die-out of fish at some sections of the River.

Facing such a severe situation, General Secretary Xi Jinping called for the guideline of “joint efforts to protect, not develop” the Yangtze. The serious illness of the Yangtze River is mainly caused by human activities, including water use, pollution discharge, navigation, power generation, exploitation and exploitation of animals and plants (fisheries, crop), mineral resources, and spaces (water-area). Therefore, human activities involving the Yangtze River should be regulated, that is to “set up the rules”. Among all the “rules”, law is the most formal and authoritative one. However, what forms a strong contrast to the need of governance of the Yangtze River by law is that, the existing laws are far from meeting this need. It’s easy to find by combing through the existing relevant laws that the laws or regulations (see table below) on different matters under the charge and leading of different governmental departments has resulted in lots of overlaps, conflicts, and blind spots.

| Laws or administrative regulations | Matters | Main content | Department in charge |

| Water Law | Water resources management | The planning, development and utilization, protection (+waters and water engineering protection), allocation and conservation of water resources, the water dispute resolution and law enforcement supervision and inspection | Department of water administration |

| Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law | Water pollution prevention and control | Standards and planning, supervision and management, and measures for the prevention and control of water pollutions (industry, towns, agriculture and rural areas, and ships), protection of drinking water sources and other special water bodies, and disposal of water pollution accidents | Department in charge of ecological environment |

| Regulation on the Administration of River Courses | River course administration | River course improvement and construction, protection, obstacle clearing and funding | Department of water administration |

| Waterway Law | Waterway administration | Waterway planning, construction, maintenance and protection | Department in charge of transportation |

| Law on Ports | Port administration | Port planning and construction, operation, security, supervision and administration | Department in charge of transportation |

| Law on Flood Control | Flood control | Flood control planning, governance and protection, the management of flood control areas and flood control engineering facilities, flood prevention and control, and safeguard measures | Department of water administration |

| Water and Soil Conservation Law | Water and soil conservation | Planning, prevention, governance, monitoring and supervision | Department of water administration |

| Land Administration Law | Land administration | Ownership and use right of land, overall planning for land use, protection of cultivated land, construction land, supervision and examination | Department in charge of natural resources |

| Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law | Soil pollution prevention and control | Planning, standards, census and monitoring; prevention and protection; risk management & control and rehabilitation (of agricultural and construction land); security and supervision | Department in charge of ecological environment |

| Mineral Resources Law | Administration of mineral resources | Registration of prospecting and approval on exploitation of mineral resources; prospecting; exploitation; collective mining enterprises and individuals’ mining | Department in charge of geology and mineral resources |

| Wild Animal Conservation Law | Wild animal conservation | Conservation of wild animals and their habitats; administration of wild animals | Department in charge of forestry and fisheries |

| Fisheries Law | Fisheries administration | Fish breeding and poultry raising; fishing; reproduction and protection of fishery resources | Department of fishery administration |

| Forest Law | Forest administration | Forest ownership; development planning; forest protection; afforestation and greening; operation and management; supervision and inspection | Department in charge of forestry |

| Grassland Law | Grassland administration | Grassland ownership; planning; construction; utilization; protection; supervision and inspection | Department of grassland administration |

| Urban and Rural Planning Law | Urban and rural planning | Formulation, implementation, revision, supervision and inspection of urban and rural planning | Department in charge of urban and rural planning |

In recent years, the Central Government and stakeholding departments have announced a series of policies and measures on the development of the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the protection of the Yangtze River, including those on control of environmental pollutions, the protection of aquatic species, the negative list of construction projects, ecological compensation, etc. These policies and measures are very focused, and have had some effects in implementation. However, they have no legal status, and managers and law enforcers face the risk of being sued against.

Anyway, the Yangtze River is sick and needs protection, and the corresponding development concepts need to be updated. The Yangtze River Basin is a complicated space involving all the aspects of both nature and society, and the rights,interests and obligations of related areas and subjects should be taken into consideration in an integrated approach based on the spatial relationship. Previous legislation methods and modes, led by governmental departments based on divisionof responsibilities, cannot meet the need of integrated governance of the Yangtze River Basin by law. Therefore, a special law is needed to protect the Yangtze River.

What are the legislative highlights of the?Yangtze River Protection Law???

First, its a response to practical needs. Nowadays, with the Yangtze River Basin as a typical example, the traditionallegislation method of “revision and amendment” cannot solve the problems of complicated systems of nature and society. Therefore, this Yangtze legislation adopted a new method and mode in response to these new problems and the need of governance by law. The Yangtze River Protection Law was drafted under the leadership of the Committee on the Protection of the Environment and Resources of the National People’s Congress, with extensive participation of stake-holding parties, based on in-depth empirical investigations and broad consultations of public opinions. This is a legislative response to the need of integrated management of the complicated system of the Yangtze River. The previous method of legislation led by sectoral governmental authorities cannot meet this need. In terms of legislation mode, this Law achieves comprehensive legislation for the natural resources and ecological environment involved in the Yangtze River Basin, including ecological protection, pollution prevention and control. The previous mode of legislation by separating natural resources (such as Water Law) and ecological environment (such as Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law) cannot cope with the complicated system of the Yangtze River Basin and achieve scientific and effective legal regulation.

Second, the Law is based on overall and systematic understanding and thinking. The Yangtze River legislation needs to respond to the complicated and difficult problems with the “natural and social” and “central and local” systems, which is a test of lawmakers and researchers’ professional understanding of the bigger picture. Therefore, it’s necessary to cross-cuttingly apply knowledges of law, society, economy, management, environment, and water management. Apart from the difficulty in understanding the system, there is the problem of multiple layers of values. The tension between economy and society, and ecological environment protection, the different restrictions of soft and hard systems, and the contradiction between the periodicity and stability of top-level design and realistic change need to be coordinated. Therefore, it’s necessary to coordinate ecological and economic interests of various subjects in each block, the overallecological interests and individuals’ rights and obligations, and to innovate regulatory framework. Aiming at these complications, and thanks to the inputs from many parties, the Yangtze River Protection Law integrates many regulations based on system thinking.

Third, the Law establishes the concept of green development. The Yangtze River needs rehabilitation. On the one hand, it’s necessary to stop excessive human activities that exceed the River system’s capacity; on the other hand, it’s necessary to follow the natural and scientific law of ecological system, and adopt measures to rehabilitate the services of the ecological system, and maintain good health of environment in the Yangtze River basin. Therefore, it’s clearly regulated in Article 3 of the Yangtze River Protection Law, “For the economic and social development of the Yangtze River Basin, ecological priority and green development shall be adhered to, general protection shall be jointly provided, and no large-scale development shall be undergone; and for the protection of the Yangtze River, coordination, scientific planning, innovation drive, and systematic governance shall be adhered to.”

Fourth, the Law bases itself on the concept of green development. The Yangtze River Protection Law has a series of provisions for, for example, evaluating the capacity of resources and the environment, making plans for green development in an integrated approach, managing the ecological environment according to “Three Lines and One List“, setting up the red line for green development; banning fishing, designating areas and periods of sand miningban, adopting supporting measures for green development; and establishing the assessment mechanism of green development.

Fifth, the institutional framework of management and governance is innovative. In terms of the institutional framework, in the background of strong [governmental] power and weak [civil] rights, the Law makes clear the issues including the responsibility division and assessment, the coordination and linkage with the existing laws, the penetration of sectoral interests, democratic guarantee, local protectionism, and legislative procedures. In terms of the institution for government accountability, he first is to make clear the responsibilities of and the division of responsibilities among government agencies in the Yangtze River Basin, including the governmental responsibilities for the planning and programming, pollution control, investment in ecological and environmental protection, compensation, and restoration of the Yangtze River Basin; the second is to make clear the assessment system for local governments (Article 79); the third is to regulate the system of admonition with local governments (Article 81); and the fourth is to regulate the system of governments’ report to the People’s Congress (Article 82), etc. In terms of basin coordination and social institutions, the first is to establish the basin coordination mechanism, which is to clearly regulate its members and the responsibilities of relevant subjects (Article 4, Article 5, etc.); the second is to establish local coordination mechanisms (Article 6, Article 80, etc.); the third is to establish the mechanism for basin information sharing and disclosure (Article 9, Article 13, Article 79, etc.); and the fourth is to establish a advisory committee made up of experts (Article 12), etc.

Sixth, the Law takes into consideration practicality. The connotation and extension of the three concepts of resource, environment and ecology are controversial in China. Some objects are not only resources to meet human beings’ needs, but also resources for ecological services. The Law protects resources through that the central government makes plansfor the Yangtze system, focusing on the protection of endangered aquatic species, evaluating the integrity of aquatic ecosystems, and establishing the genetic bank of wild animals and plants. It prevents and controls pollution by controlling the total quantity of discharge, strengthening the supervision of solid wastes, reinforcing the prevention and control of agricultural diffusive pollution, assessing aquifer pollution and other environmental risks, managing and controlling the transportation of hazardous chemicals strictly, relocating hazardous chemicals industries in key areas, etc. Meanwhile, it incorporates ecological security, prioritise ecological integrity, brings forward specific measures for ecological protection, and clarifies compensation system for ecological protection.

Seventh, the Law clearly defines responsibilities and obligations, and urges participation. By defining the responsibilities (governments)/ obligations (civil subjects), rights (civil subjects) /power (governments) and legal liabilities of relevant subjects, the law encourages extensive public participation in the governance of the Yangtze River by reasonably arranging a series of systems and measures to achieve the joint management of the Yangtze River.

Eighth, this Law combines legal evolvement with continuity and stability. It not only meets the special need of managing the Yangtze River by law, but also maintains the linkage with the existing laws. Through the combination of general provisions and special provisions of legislation, it highlights uniqueness of the Yangtze River Basin, but also pays attention to its linkage to general laws at the same time.

You mentioned that the?Yangtze River Protection Law?is a manifestation based on systematic?understanding, and involves a very complicated long-term process. Instead of an end, many people said that the Yangtze River Protection Law is?a?start?of the efforts to protect the River. This Law brings forward many good principles and concepts. What aspects do you?think, as an expert closely involved in the legislation process, we?should?prioritise?in the implementation and improvement of the Yangtze River Protection Law???

The first is understanding and assessment. Through interdisciplinary approaches, we should comprehensively apply the knowledges of hydrology, hydraulics, ecology, soil science, related resource science, economics and law for a comprehensive and clear understanding of the complicated “nature-society” system of the Yangtze River Basin, including both overall and localised understandings (the upper, middle and lower reaches, the estuarine areas, both banks),. It also includes economy and livelihoods in the Yangtze River Basin, and the pressure brought by them to the natural system based on solid empirical research, and cost-benefit appraisal of resources utilisation and eco-environmental protection.

The second is planning and control. We need to make a master plan for the Yangtze River Basin based on scientific understanding and appraisal. This plan should give reasonable considerations to the ecological and environmental protection, and the people’s livelihoods and economic development on the upper and lower reaches, the left and right banks, and at the main stream and tributaries of the Yangtze River Basin. It has to link itself to the national plans for the development of national economy and society, with the latter gradually “greened”. It also needs to be implemented inalignment with the territorial spatial planning, various special planning, and regional planning in the Yangtze River Basin, all of which should not go against the master plan. There are some issues to be solved herere, for example, who should prepare the master plan? How should it be prepared (scientifically and reasonably)? How could it be linked with the existing plans? How should the conflicts, if any, be solved? What about the legal liabilities if certain subjects haven’t prepared and implemented the territorial spatial planning, various special planning, and regional planning of each placeaccording to the requirements of the Law?

On the basis of these planning, we could manage the territorial space of the Yangtze River Basin by area and different use,make overall arrangements for the reasonable allocation, unified dispatching and efficient utilization of natural resources in the Yangtze River Basin, control the total pollutants discharged, and implement other measures to guarantee the ecological health and security of the Yangtze River Basin. These systems and measures will surely face many problems in implementation, and will be improved in the process of “implementation”-“discovering problems and finding solutions in legislation”-“improving legislation”-“re-implementation”.

The third is industrial structuring and green development. It’s not easy to achieve the above-mentioned objectives in the Yangtze River Basin, and wherein, one of the core issues therein is population and economy. While supporting theeconomy, the Basin has formed this spatial layout of industries: The upper reaches form an important ecological barrier, but receives much pressure because of poverty. In the middle and lower reaches, the developed economy and culture and the dense population (especially in mega cities) have led to the increasing pressure on the natural system, yet the economies of small cities are declining. There are lots of industries with high pollution, emissions and energy consumption. There are still a large number of low-end industries. To sum up, the tension between the people’s livelihood, economy, ecological and environmental protection in the Yangtze River Basin is very big, and it is caused by different factors in different sections and on different levels. The pragmatic countermeasure should be to, on the basis of surely meeting the needs of the people’s livelihood and economy, based on the overall vision and thinking of the Yangtze River Basin as “a game of chess”, and aiming at the above-mentioned problems, upgrade industries, adjust layout, revitalize small cities, promote the communication and cooperation between the urban-rural areas, eastern-central-western regions, and the two banks of the River, and coordinate their development. In this respect, there are many issues that deserve further study.

The fourth is the institution suitable for the protection of the Yangtze River, which is a key point to the Law. TheLaw has set up a series of institutions for governments, basin coordination, social co-governance, etc., and has up to 65 articles regulating the responsibilities of the Central Government and its departments, as well as local governments and their organs. Still, there are lots of work to do to practically implement the written provisions on institutions in this Law. In addition, many issues on system and mechanism are worth further study, such as the division and linkage of the Yangtze River Basin’s authority, central authority and local authority, the legal status of the Yangtze River Basin, and the party representing the Yangtze River Basin.

The fifth is the linkage between the Law and other laws. The Yangtze River Protection Law is a special law made in response to the special need of joint protection of the Yangtze River, and it has many major differences from the existing laws in terms of legislation concept, method and mode, adjustment object and method, institutional frameworks and measures. For example, what if the administrative law enforcement and judicial control are not consistent with existing legal provisions, and the methods conflict? Just to have an example, it’s regulated in Article 6 of the Yangtze River Protection Law that, “The relevant regions in the Yangtze River Basin shall establish cooperation mechanisms in the formulation of local regulations and government rules, preparation of plans, supervision and law enforcement, and other aspects as needed…”, so how to deal with the local regulations in the Basin according to national laws which have taken effect? What if the national laws (some of which are made and promulgated by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and have higher validity) used as basis are inconsistent with the Yangtze River Protection Law? All these problems need to be solved gradually in the implementation of the Yangtze River Protection Law.

It’s regulated in Article 2 of the?Yangtze River Protection Law?that,?“The ecological and environmental protection and remediation in the Yangtze River Basin and the various production, living, development, and construction activities in the Yangtze River Basin shall comply with this Law.”?However, the?flows?of resources in the Basin, including water,?food?and energy, may not be limited to?it?because of?other?paths?such as South-to-North Water Diversion, West-to-East Natural Gas Transmission, food?transportation. So?how?should these problems be solved given the effect of?the?Law??

First, the Yangtze River Basin is a concept of a big space. According to the provisions of the second paragraph in Article 2 of the Yangtze River Protection Law, “Yangtze River Basin means the drainage area of the main stream and tributaries of the Yangtze River and lakes, incuding Qinghai province, Sichuan province, Tibet Autonomous Region, Yunnan province, Chongqing Municipality, Hubei province, Hunan province, Jiangxi province, Anhui province, Jiangsu province, and Shanghai Municipality, as well as certain county-level administrative areas of Gansu province, Shaanxi province, Henan province, Guizhou province, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Guangdong province, Zhejiang province, and Fujian province.” This is a very big spatial scope.

Second, it’s regulated in the first paragraph of Article 2 of the Yangtze River Protection Law that, “The ecological and environmental protection and remediation in the Yangtze River Basin and the various production, living, development, and construction activities in the Yangtze River Basin shall comply with this Law.” “The ecological and environmental protection and remediation in the Yangtze River Basin and the various production, living, development, and construction activities in the Yangtze River Basin” includes all ecological and environmental protection and rehabilitation, production and living, development and construction activities implemented in the Yangtze River Basin. If the water, gas or food as you mentioned is produced in the Yangtze River Basin, even partially in terms of space and time, they shall all be within the scope of the Yangtze River Protection Law.

An important part of the?Yangtze River Protection Law?is the disclosure and sharing of information, but at present, we still need great improvements in data disclosure. What do you think is the crux of our problems at present? How shall we solve the current barriers to information sharing by taking the opportunity of thislegislation???

It’s regulated in the first paragraph of Article 9 of the Law that, “On the basis of existing monitoring networks, the National Yangtze River Basin Coordination Mechanism shall coordinate the improvement between relevant departments of the State Council to improve the sharing mechanism of information about the ecology and environment, resources, hydrology, meteorology, shipping, and natural disasters.” It’s regulated in Article 13 that, “ The National Yangtze River Basin Coordination Mechanism shall coordinate the establishment and improvement of an information sharing system for the Yangtze River Basin between the relevant departments of the State Council and the provincial people’s governments in the Yangtze River Basin. The relevant departments of the State Council, the provincial people’s governments in the Yangtze River Basin, and their relevant departments shall share information on the ecology and environment, natural resources, and administration and law enforcement in the Yangtze River Basin as required.” Article 8, Article 46, and Article 79 regulate the information disclosure system.

The sharing and disclosure of information has great significance for the timely and accurate grasp of the Yangtze River Basin’s dynamics and relevant parties’ behaviours affecting the Yangtze River. This is crucial for stake-holding governments and departments to participate in the integrated management, law enforcement and judicial protection, and for stakeholders’ full-process participation in decision-making, implementation and supervision.

The premise for the disclosure and sharing of information is the acquisition of accurate information. There is still lots of work to do in this aspect. Let’s take the construction of monitoring networks as an example. Previously, different governmental departments established their own monitoring systems for different purposes, so the monitoring networks are overlapping, conflicted, and of course have blind spots. Based on the concept of integrated management, the Yangtze River Protection Law regulates “improving the monitoring network system for the ecology and environment, resources, hydrology, meteorology, shipping, and natural disasters in the Yangtze River Basin”, providing a legal basis for the construction of monitoring network system. However, there are still lots of practical problems, and it requires a certain process for the scientific establishment of such a monitoring network system.

The improvement of the mechanism for sharing of monitoring information is only generally regulated in the Yangtze River Protection Law, and it needs to be regulated in detail in supporting laws and regulations, for example, how to share monitoring information (what platforms to transmit to? Who has the right to obtain the information of the platforms, based on what qualifications and through what procedures)? What responsibilities (entity provisions and procedural provisions) shall be implemented by government agencies for realising the sharing of monitoring information? What is the consequence of failure to implement statutory responsibilities?

There are more problems with the disclosure of information. On April 3, 2019, the State Council made major revisions of the Open Government Information Regulation, but still, this Regulation needs to further define the subjects, scope, procedures and methods of the governmental information disclosure, and the legal consequences of failure to implement the responsibility of information disclosure.

Finally, which of the ideas, principles and experiences behind the Yangtze River Protection Law do you think can be transplanted to other basins in the future? Whether we can summarize some common things from these to form a general basin protection law of our country in the future?

First, different basins have their common and unique characters. Please allow me to illustrate the unique characters by a comparison between the Yangtze River and the Yellow River. Both the two rivers are Mother Rivers in China. Comparatively, there is plenty of water in the Yangtze River Basin, but less water in the Yellow River Basin. Yangtze River doesn’t have a high sediment load, but that’s very high in the Yellow River. The economy is better developed in the Yangtze River Basin, especially in the eastern regions, but undeveloped in the Yellow River Basin… Therefore, the legislation for the Yangtze River Basin and that for the Yellow River Basin are surely different in terms of concept, guiding principles, ideas, and content. The Yellow River Basin is inferior to the Yangtze River Basin in terms of economic development and natural conditions, so in the legislation for the Yangtze River Basin, the word “protection” is added in the front. As far as I’m informed, the legislation for the Yellow River Basin is in the process at present, but the word “protection” may not be added, and it will probably be the Yellow River Law.

Second, to make a general basin law, the premise should be satisfied, which is to have certain understanding with and accumulation of experience in the legislation for specific basins. If we’re not clear about the situations and needs of governance by law in different basins, how shall we generally abstract their common principles and systems? So we should find out the details and accumulate experiences by starting with a specific basin, and then conduct general basin legislation through summarisation and abstraction. With a general basin law, we won’t have to rewrite all contents for every specific basin. This is a combined bottom-up and top-down method, and from the perspective of philosophy, it is a method of combining empiricism with rationalism.

]]>

I just can’t help buying more

How much water you need to consume each kilogram of these

What is virtual water and the water footprint? How is the trade of virtual water relatable to the increasing pressure on global water availability?

So maybe firstly, I can put things into a bit of context by travelling a little back, and explain why virtual water and the water footprint are important. I first got interested in this topic and global water security in about 2005, when more and more countries across the world were having more and more reports and documents written on water security. I was invited to join a Royal Academy of Engineering committee to deliver the report as the outcome of our investigations on global water security. I learnt a lot in that task, and I found it equally rewarding as my research activities ever since. So I’ve given many talks on this topic.

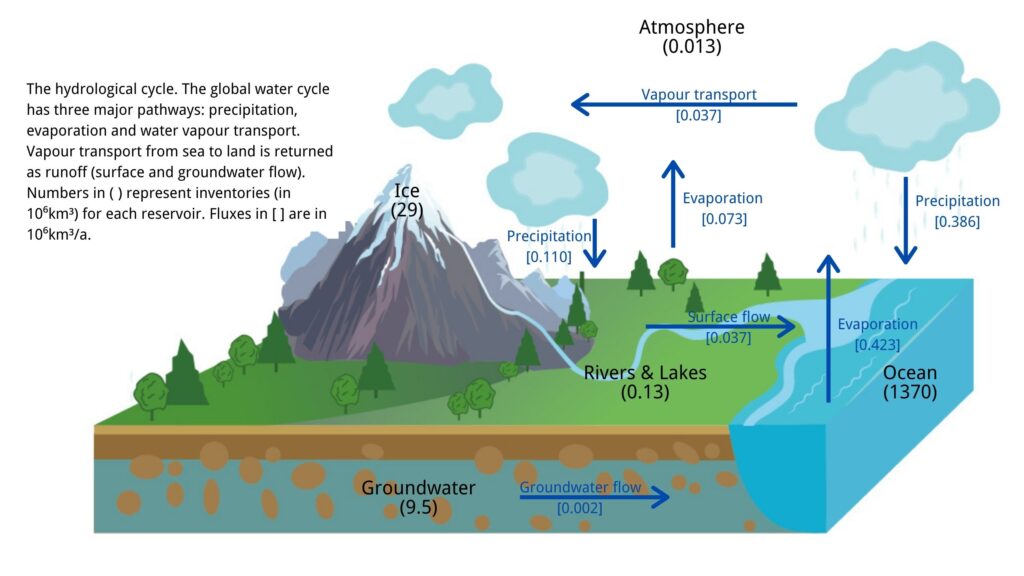

In the water cycle, we have water coming from the clouds that stay above the mountains. It then falls down as rain onto the land, then flows through the rivers as blue water. It can be absorbed in soil as green water, which can later be converted into grey water. So for a typical huge catchment, from the top of the catchment down to the coast, if we say that the rain that falls on the land is 100%, only about 36%, on average, would end up in the ocean. So what happens to the rest? We take off water from the river. The water we take off could be for domestic consumption. So it comes into the homes for showering, washing the dishes, washing clothes, and so forth. If you take that out of your river in your country, it’s your water. You’re using it and it’s up to you to clean it before you put it back in the cycle. The other thing is, though, a large amount of water is taken off the river to produce products. So it could be for paper, a car, or crops like cotton. So you do this in your country X, China, for example. You then use a large amount of water to produce, shall we say, your cotton. I’m going to use cotton as my example, if I may, because we have no cotton production in the UK. So you produce cotton, and then you manufacture clothes and sell cotton products into the UK, for example. You’ve used your water in your country to produce cotton. So when I buy a cotton shirt, and let’s assume the shirt is made in China, then all the water that has been used in manufacturing that shirt is your water. We call that virtual water of products and which has been manufactured through the use of your water.

So when we talk about the water footprint of a nation, there are two components. We have the internal water footprint, which is the water in my country, for example. It’s used in my country to feed the animals, for example, which are reared for food and then meals. The external water footprint is the water used in another country, let’s say, New Zealand, for example, which produces lamb purchased in my country. That’s virtual water. That is known as the external water footprint. Equally, we could supply goods from my country to China, for example, in which case we are using our water to produce goods to be sold to China. So the total water footprint of a nation is equal to the water used internally, that’s our own water, plus the virtual water import, that’s the water we use in China or India or Egypt to produce cotton for our country, minus any products we produce in this country using our water to sell overseas.

The first problem we have to get into perspective is that there?is?actually a lot of water on this planet, about 1.4 billion cubic kilometres. However, the salt water doesn’t help us in terms of water supply for domestic use, and it doesn’t help us in agriculture or food production.?So we’re left with 35?million?cubic kilometres of fresh water, and most of that is in ice, which is?not readily available for us to use.

The natural hydrological cycle (data source: Hydrogeology: Principles and Practice, Hiscock and Bense, 2015)

We also need to bring into perspective the water–food–energy nexus. We need water to produce food; we need food to give us energy as human beings; we need water to move energy; and we need energy to move water around cities, for example. So this link between water, food and energy is crucial. Once you change one component of the nexus, you have a knock-on effect on either food or energy production. The problem is, at the moment, we only tend to focus on the water-food-energy nexus in our own countries. So people in the UK, for example, focus on questions like do we have enough energy or water here to meet our needs in the UK, or do we have and can we import enough food to satisfy our needs? And that’s the big issue.

There are some major pressures, which we have to put into context as well. We have to look at this problem of virtual water and water availability, and the stress that we could face more and more in the future around two key issues in my view. One is climate change. At the moment, we’re expecting the global temperature to increase, by the end of the century, by typically three to four degrees. The IPCC and many countries across the world, including China, are doing everything they possibly can, to reduce the reliance on fossil fuels, and try to get this temperature increase down to one to two degrees by the end of this century. That is not going to be easy. But even a one to two degree increase is going to give us a lot of additional water stress across the globe, including in the UK. The other issue, which is not often talked aboutbut can’t be ignored, is population growth. If you just take the UK for example, when I was born nearly 70 years ago, the population of the UK was only about 50 million. It’s now up to 66 million. The global population is rising. It’s currently about 7.5 billion on the planet, and is expected to rise to about 11 billion by the end of this century. So we will have to find, typically 50% more food, and for that we need more water, and we also need more energy.

Not only that, we also have a big shift in the population. In more and more countries across the world, including China, from my experience, the population is moving from the rural areas to the urban areas where the jobs are. So, the cities are getting larger and larger and we are having more and more mega cities. Most of these mega cities around the world are built right around estuaries, for example, the Thames, or on the coast. Shanghai would be an example in your country. People are becoming richer globally. China is a very good example. I have been coming to China since 1984, which was almost 40 years ago. I’ve noticed a huge change in the wealth of citizens in China. People’s diets are changing too. One kilogram of beef, coming to the water footprint, requires 15,000 litres of water to produce, while one kilogram of wheat only requires 1,300.

There are a couple of other points as well. 70% of freshwater at the moment is used for agriculture. So if we’re going to face increasing water stress in the future, how are we going to make more food? Then we will have to look at how we can make agriculture more efficient.

If I may, I’d like to digress slightly here. The world is seeing considerable investments in things like the aircraft industry, including more efficient aircraft engines, and so forth, so that more and more people have been flying, though pre-COVID obviously. Investments globally in this area are enormous. I could take many other examples, the car industry, Formula One cars and so forth. The cars have developed and transformed enormously in my lifetime. However, you see agriculture, the way in which we produce food today, is still pretty basic. We’re not really getting much more crop per drop [of water] than we did almost when I was born. That’s because it’s not seen as a particularly attractive subject to the brightest students in universities. They see developing the next Rolls-Royce or General Electric engines for the aircraft to be more efficient and so forth as very attractive. But I don’t think they see agriculture, and optimizing the crop per drop that we can get out of agriculture as particularly attractive. So you have to change this. This is, I think, is important in the context of virtual water.

We have countries like the UK for example, which is very developed. But you have to look at many other parts of the world where we see a huge amount of people suffering from health problems and even death due to water problems. We have to be mindful of this when we talk about virtual water. So let me just take a couple of examples here. 1.2 billion people on this planet have no access to safe drinking water, and 2 million young children die every year of diarrhoea. Most people in my country won’t be able to imagine that and it’s very rarely referred to in the media. Yet, if you just take the COVID crisis for example, I don’t know what the exact figures are now, but the number of deaths in the US is about a quarter million. However, the topic of COVID-19 has been on British television, day in and day out, for the last nine months. It has taken up, probably without any exaggeration, a third of the news reports. And yet the number of deaths due to COVID-19 is small compared to the number of children that have died in the same period, mainly in nations in Africa, due to very simple health problems, diarrhoea, for example, something we can solve quite easily. It’s not like a new virus like COVID-19 and so forth, where the whole world is desperately trying to get a vaccine. Without basic access to water and sanitation, women in developing counties typically walk six kilometres to get water for the children and family.

So we have the sustainable development goals (SDG). Then we have the water-food-energy nexus so that sustainable development goals, I should say, were to address. If you look at Goal 6 in particular, which is relevant to virtual water and the water footprint, the Goal is to provide access to safe and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all. That is a big challenge. I don’t think it’s presently achievable in 2030, even without COVID-19. Affordable and safe drinking water, in continents like Africa, is going to take more than 10 years to achieve in my personal view. Even in my own country, water quality in many rivers here is still of strong concern. To increase water efficiency and address water security, we need to look well beyond that, we need to consider what can do to reduce our virtual water consumption in the UK, for example,to make more water available in other countries, like Egypt, or India, and so forth. We need to ensure that grey water is cleaned before returning it to the river so that people can use clean water for sustainability in their own countries. We need to protect and restore the water ecosystem, and we need to expand international cooperation. That’s why I value my links with China, because we can learn a lot from China, and I think we have a lot to offer China as well. We also need to strengthen participation in the water and sanitation management.

When we look at the UK, for example. I hope you don’t mind me referring to the UK. It doesn’t matter. The principle is the same. We have a very high rate of consumption of water. A typical British citizen, me for example typically uses 150 litres of water a day. That’s the amount of water that comes into my house, that I use in a day, to shower, to wash my clothes, to make my meals, and so on. But my total water footprint, when you consider all of the commodities I’ve have in my home, the cars and so forth, is 4.5 cubic metres per day, in other words, 4,500 litres per day. So my domestic consumption, which everybody’s trying to reduce now, through not leaving the tap running while you’re cleaning your teeth, for example, is really small by comparison. The UK is one of the worst countries. So most of our daily total footprint, including virtual water, is extremely high. So we have in my country a huge responsibility to protect water security in the countries that supply us with products.

Now, let me talk about the water footprint. You’re talking about how much water is needed in total to produce commodities. So for example, if I have a cup of coffee, the total amount of water that’s been put into producing this coffeeto make this cup of coffee, or to make coffee beans, is 150 litres. So when I buy a cup of coffee from a store, I have consumed or effectively consumed 150 litres water. If that coffee comes from Brazil, for example, almost all that water is from Brazil as well. When we turn to a cotton shirt, for example, that tends to come from places like India, Egypt, Uzbekistan, and so forth. We have had a huge impact on those countries. In the UK, if you are producing crops, you will be using pesticides and so forth, and the water will be cleaned in general, not perhaps to one hundred percent by any means, before it goes back into the river. One of the reasons that I’m concerned is that, I can buy at a relatively cheap price, a shirt, made of cotton, produced in other counties like India or Egypt or another country. The problem is that, the water is contaminated through producing the cotton to make that shirt. It then goes back into the river, probably not treated that much. Then downstream in the river, it has a knock-on effect on the health of the people depending on the river.

So all the products we consume have water footprints. Under the growing pressures you have mentioned, how could water footprint be lowered?

So we have to ask, how can we reduce our total water footprint, which, in my view, is to do with our culture. Let’s takeChina; over the 40 years I’ve travelled to China, it has also changed its culture to follow many of western habits. For example, if I look at a man and a woman reading the news, the man could wear a grey suit, a white shirt, and a blue tieevery day. He can wear that on Monday, on Tuesday, on Wednesday, and on Thursday, not necessarily the same shirt though. Nobody in my country would criticize him for being boring because he is in the same clothes every day of the week. I don’t think we ever saw, Barack Obama, the former US president, in a picture when he didn’t wear a dark suit and white shirt, and he was photographed on television in my country probably two or three times a week. In contrast, to go back to the news reporter in the UK, the woman would be expected to put on a different dress every day of the week, and that dress might be made of cotton that was manufactured in countries other than the UK. Its production might be contaminating downstream water. I ask myself, should I be paying more for the shirt or should my wife be paying more for her dress, so that we could use that extra money in those countries to treat the water before it goes back to the river? I believe this is very important because I think it would lead to much better and sustainable water quality.

If we’re going to address the Sustainable Development Goal 6, I believe this is a really an important factor. So why does a man manage to maintain a high profile in work in the same clothes, which could be the same outfit every day, sort of almost a uniform, and yet a woman is expected to wear different dresses daily. Everybody in the UK is walking around in clothes with a high cotton content. The 66 million people in my country are having a huge impact on water security in many countries across the world from which we import cotton. So again, if I just take another example of a wedding in this country. I could wear the same suit every time to the wedding of my children and no one is going to question me for that. They would [only] say, “Roger, the same suit from last time.” But our friends coming to the wedding would expect my wife to wear a different dress. Usually those are very expensive wedding dresses too.

So it is something I think belonging to western culture. We would never see senior female figures in my country, members of the royal family, for example, wearing the same clothes regularly. When I first came to China in 1984, all the men were dressed the same, and all the women were dressed the same too. The women didn’t have any makeup on. So in terms of water security and water management, one of the best practices or policies to adopt in a country is to encourage people not to change their clothes every day. It’s the change in habits and culture, which took place in the last hundred years or so in my country, or the last 30 or 40 years in China, during which I’ve noticed big differences. For example, when you walk down the high street in China now, which is just like walking down Oxford Street in the UK, every woman has a different dress on. I don’ think this is wrong, but we have to be aware of the fact that by adopting many of these habits, you’re having very significant impacts on water security in other countries.

Based on your ideas, it appears that global sustainability is closely hinged on our culture and social norms. What roles can the public play in minimising our water footprint? How should scientists and researchers catalyse changes for better and social norms and water governance?

Let me deal with the scientific issues first if I may. On the scientific front, let me go back to the example of agriculture. You know most of our water is used for agriculture. I mean agriculture in the broadest sense, which includes agriculture for producing wine, raising animals like cattle and sheep, growing crops and so on. At the moment, the way that crops are grown in this country, let me take lettuce, for example, or cabbage, or any green crop that you eat? It’s planted in fields which could take up a lot of land. The water falls down on these fields. Much of that water goes straight into the soil and falls straight through soil into the ground water, and only a small percentage of that water is used to actually grow the crops.

Now, some countries, particularly the US, are using what they called ‘vertical farming’ or hydroponic farming. You will grow your crops vertically so you’re not using that much land. The crops are grown vertically in a room, which is like a very large glass house or factory, but with operating theatre standards in terms of health. It’s almost like an operating theatre on a hospital ward with COVID patients. You will have to go into the room fully protected. There are no pesticides inside. You don’t need chemicals to treat the plants. The figure I’ve got in front to me, states that it only requires 1% of water to produce the same number of crops as the amount of water needed for producing those crops on land. It’s 350 times more efficient producing crops from land. It doesn’t require any pesticides. The rooms are controlled with humidity, temperature and so forth, which provide perfect growing conditions for lettuces, cabbage and those sorts of crops. So on the scientific side, there are huge developments ongoing in agriculture in that area. On the other side, I think, talking to the public can also have a huge impact.

People like us have a responsibility to educate the public. So if I’m asked to give a talk to an academic audience, to IAHR for example, I’m very happy to do that, and we could discuss technical issues such as looking at faecal bacteria prediction models etc. Again, I get as much satisfaction these days talking to a complete lay audiences. In my view we could have a significant influence on the public to change their behaviour and water security on this planet. Let me give you an example. We have coffee in my country being produced in various countries in the world which I won’t name. It was almost slave labour, very cheap labour. People couldn’t even exist in their own country on the income received. It was promoted on television about major companies buying coffee from these countries and then selling it in the UK. It shocked the public to think they were buying coffee, paying quite a lot of money for it, and the people that were collecting the beans and so forth in other countries were not getting paid much for collecting the coffee beans. It’s almost slave labour. Then we had an initiative from the public in that they would not buy coffee from shops unless they had a sign outside saying ‘fair trade coffee’. In other words, they had to guarantee that the companies buying that coffee were ensuring that the people that were collecting beans and so forth were actually getting paid a decent wage. So the public would put pressure on companies to ensure that they were paying employees right down the train a fair wage. Similarly when I buy a shirt, for example, I would like to know that a certain amount of that money is being used in the other country where the shirt is produced to clean the water up after the shirt is produced before it goes back into the river. I would rather pay more to a company that can convince me, or reassure me, that the water is treated after it has been used to produce that shirt, so that the water returned to the ecosystem is of high quality. I believe that with enough public pressure companies would be required to make sure that the water is treated before it goes back into the river.

If I walk into two shops, one tells me I’m buying coffee from fair trade and people collecting the coffee in a 3rd world country are getting a fair wage, then I would rather go into that shop than the one next door, which is not offering fair trade coffee. Likewise, if I’m going to prefer to buy a shirt from a shop where they can guarantee me that the water is treated before it goes back into the river. Here I would rather pay more for that shirt than go to another shop next door which can’t give me that guarantee. That will come from public pressure. I believe that the more we can educate the public on water security globally, about the impact we have in Britain in buying coffee, for example, on the water security in another country, then the more pressure the public will put on companies to make sure that we are looking after the people in the country where they are buying the coffee from.

I think if you educate people in China, China could set a very good example to the rest of the world, and could lead the world in this regard. Bear in mind that if you buy products from other countries, expect the water to be treated properly before you buy it. As a foreign member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, I’m more than willing to contribute to this debate.

You have mentioned the inequalities between genders in terms of both water access and water footprint, and hence different implications for virtual water flows. How could we mitigate such inequalities in the broader sphere of water security and sustainability?

When I come to gender issue, I think this is the greatest opportunity of all to attract more women into engineering. We have many people in my country, trying to get more and more women into engineering, to improve our productivity and so forth. Women are very good at mathematics in general, just as good as men. They have just as much opportunity to contribute enormously in engineering as do men. Let’s take the Formula One as an example. I don’t know much of the details but I happen to watch the Formula One. I can imagine lots of young people thinking “I would really like to get involved in modelling aerodynamics for improving the engine of the Formula One car.” I’m sure that Ferrari would be keen to pick up any really promising engineer to help improve their car to ferociously compete with Mercedes next year. That’s very attractive to men in general. Young, high-flying, male students would be very attracted to improving that Ferrari car, feeling that they’ve achieved something. But is it that fantastic to have made that achievement? I would say not. The trouble is if you turn round and say, well, can we persuade that really bright man, not so much to spend his time on getting the Ferrari engine and the design of the car to be much more competitive? Would it not be better to persuade him to focus his brain on developing better agricultural systems, so that we could obtain a more efficient agricultural system? That’s so not going to be particularly attractive to women either.

Two million children are dying every year in Africa of diarrhoea, a very basic disease. Hardly anyone dies from diarrhoea in the western world. If I turn round and say to women in my class when I was teaching students at Cardiff University – you could actually save huge numbers of lives if you take your excellent academic skills and try to improve the crop per drop, we can get more food out of the limited water resources we have on this planet. You could reduce food shortage and poverty dramatically in many countries. If you put your minds to developing improved hydrodynamic modelling, biochemical modelling, ecological modelling and so forth, so that we can focus on improving the quality of water at the plant, at the farm before it goes back in the river, you could save thousands of lives downstream because the children downstream bathing in the river will be playing in water with much better quality. Then you could persuade women to come into engineering and use those brains actively to improve the water quality from the cloud right down to the coast. And then agriculture suddenly becomes very attractive because the deliverable at the end of the day is improving the water quality in the system from the catchment down to the coast, improving public health and saving lives. You would probably save more lives as an individual than any doctor would in his or her lifetime, even if we left the boys carry on trying to improve the efficiency of Formula One cars.